File formats reverse engineering: Difference between revisions

More actions

No edit summary |

|||

| (14 intermediate revisions by 4 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

= Reverse | = Reverse of File Formats = | ||

This page is intended for research on reverse engineering file formats and ongoing experiments. | |||

== | == Archives / Compressed Files == | ||

The "[http://wiki.xentax.com/index.php/DGTEFF Definitive Guide To Exploring File Formats]" is a good starting point for understanding file organization. We can potentially create a list of possible fields that may appear in the header of the studied file to identify different header elements and their functions. | |||

== Variable Typing == | |||

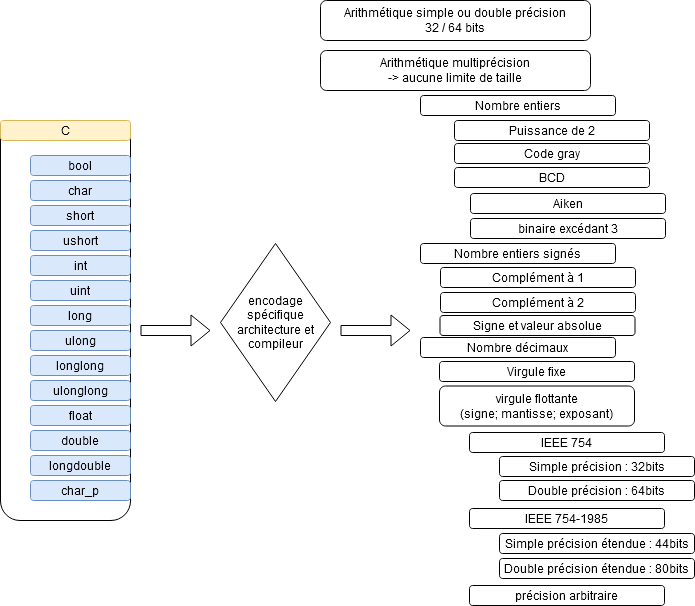

[[File:Typage & compilation.png|800px|center|thumb|thumbnail]] | |||

When studying files that structure data from a program, it's important to keep in mind that types are translated by the compiler for a specific architecture. As a result, the same value can be represented in binary in different ways. | |||

=== | == File Sizes == | ||

=== GCD and File Size === | |||

The idea here is to observe file sizes to identify characteristics of certain archives, such as header size and the possible use of fixed-size "containers" or chunks. | |||

To do this, we take all the file sizes in bytes of each file in the studied format. We calculate the greatest common divisor (GCD) of these sizes, and if the GCD is significant, it indicates a potential header and chunks of size equal to the GCD. | |||

=== GCD and Variable Header Size === | |||

In cases where a file has a header size different from the chunk size, we can test GCDs by subtracting an increasing header size. | |||

The structure of the searched file would be as follows: | |||

|---- HEADER ----|------------ CHUNK 1 ------------|------------ CHUNK 2 ------------|------------ CHUNK N ------------| | |---- HEADER ----|------------ CHUNK 1 ------------|------------ CHUNK 2 ------------|------------ CHUNK N ------------| | ||

We will use a threshold above which we will display the header size and GCD. | |||

== Searching for Known Properties == | |||

=== Brute-Force of a Fixed Offset === | |||

In cases where we can gather a set of properties that can be clearly attributed to a group of files, it may be possible to brute-force to find the location in the file where these properties are stored. | |||

The first step is to search for a set of data to gather them into a CSV file. These data should be associated with a file name. For example, we can scrape this data from fan websites. | |||

The second step is to program the search for many coherent encodings for each property in the CSV. We will search for all these encodings in all files from position 0 to the end of the smallest file in the set. Then we will check if the property appears at the given position. If it is not present, we will move to the next position. | |||

It's important to note that types are translated differently by compilers. We should test different representations (signed numbers in one's complement, two's complement, sign and absolute value, fixed-point, floating-point, with different sign/mantissa/exponent sizes, etc.). | |||

=== Sets and Masks === | |||

Here again, we have a dataset with properties related to the studied files. The goal is to group properties by values and study changes in associated files to identify the potential position of a property. | |||

For files: | |||

A = Set(files WITH value "a" for the property) | |||

B = Set(files WITHOUT value "a" for the property) | |||

D = Mask file # of the same size as the file; we will put FF or bits set to 1 in places where the bit or byte may represent the property | |||

For all A, if the byte at the studied offset is identical, we set the byte in D to FF; otherwise, we set it to 00. | |||

For all B, if there exists a B that is identical to the byte in A, we set the byte in D to 0x00. | |||

We repeat the operation for all values of the property. To add flexibility, we can introduce error tolerance for a dataset that may contain errors or the presence of specially encoded values. | |||

The bit-wise approach poses an issue in comparing A and B. If the byte at position i is identical for A and B, then we remove the byte from the mask. But for bits, we need the exact size of the property's encoding because if the bit size is smaller, we may find values that are potentially identical for A and B, with the next or previous bit belonging to the property and differing. The same issue applies if the bit size is larger. | |||

This is why it's necessary to create multiple masks for each bit size. Randomly added similarities or differences with an incorrect bit size of the property's encoding nullify the mask, so we test by incrementing sizes and keep only the mask that produces a result. | |||

It's also important to note the overlap of the mask after a shift. For example, if we study bits from 0 to 4 and set the mask to 1111, we will subsequently study bits from 1 to 5 and potentially get 10000, which would erase the previous work. The idea would be to force bits to 1 and not reset them when they are set to 1 in the A and B comparison. We can potentially create two masks A <-> A and A <-> B and then use the logical AND. | |||

== Tools to Test == | |||

https://hexinator.com/ | https://hexinator.com/ | ||

https://www.sweetscape.com/010editor/ | |||

Test entropy with binwalk (1. in Doku). | |||

== Doku == | == Doku == | ||

[https://archive.fosdem.org/2021/schedule/event/reverse_engineering/attachments/slides/4518/export/events/attachments/reverse_engineering/slides/4518/Reverse_Engineering_of_binary_File_Formats.pdf Reverse Engineering of binary File Formats] | |||

[http://www.iwriteiam.nl/Ha_HTCABFF.html http://www.iwriteiam.nl/Ha_HTCABFF.html] (Tools extraction is pending from the links) | |||

https://github.com/tylerha97/awesome-reversing (A comprehensive list to study, determine what relates to binary reverse engineering - see if there are other "awesome .." lists) | |||

https://beginners.re/RE4B-FR.pdf (check the detailed table of contents and find sections related to binary reverse engineering) | |||

https://en.wikibooks.org/wiki/Reverse_Engineering/File_Formats | https://en.wikibooks.org/wiki/Reverse_Engineering/File_Formats | ||

[[Category:File format]] | |||

[[Category:Gotcha Force]] | |||

Latest revision as of 10:18, 20 September 2023

Reverse of File Formats

This page is intended for research on reverse engineering file formats and ongoing experiments.

Archives / Compressed Files

The "Definitive Guide To Exploring File Formats" is a good starting point for understanding file organization. We can potentially create a list of possible fields that may appear in the header of the studied file to identify different header elements and their functions.

Variable Typing

When studying files that structure data from a program, it's important to keep in mind that types are translated by the compiler for a specific architecture. As a result, the same value can be represented in binary in different ways.

File Sizes

GCD and File Size

The idea here is to observe file sizes to identify characteristics of certain archives, such as header size and the possible use of fixed-size "containers" or chunks.

To do this, we take all the file sizes in bytes of each file in the studied format. We calculate the greatest common divisor (GCD) of these sizes, and if the GCD is significant, it indicates a potential header and chunks of size equal to the GCD.

GCD and Variable Header Size

In cases where a file has a header size different from the chunk size, we can test GCDs by subtracting an increasing header size.

The structure of the searched file would be as follows:

|---- HEADER ----|------------ CHUNK 1 ------------|------------ CHUNK 2 ------------|------------ CHUNK N ------------|

We will use a threshold above which we will display the header size and GCD.

Searching for Known Properties

Brute-Force of a Fixed Offset

In cases where we can gather a set of properties that can be clearly attributed to a group of files, it may be possible to brute-force to find the location in the file where these properties are stored.

The first step is to search for a set of data to gather them into a CSV file. These data should be associated with a file name. For example, we can scrape this data from fan websites.

The second step is to program the search for many coherent encodings for each property in the CSV. We will search for all these encodings in all files from position 0 to the end of the smallest file in the set. Then we will check if the property appears at the given position. If it is not present, we will move to the next position.

It's important to note that types are translated differently by compilers. We should test different representations (signed numbers in one's complement, two's complement, sign and absolute value, fixed-point, floating-point, with different sign/mantissa/exponent sizes, etc.).

Sets and Masks

Here again, we have a dataset with properties related to the studied files. The goal is to group properties by values and study changes in associated files to identify the potential position of a property.

For files:

A = Set(files WITH value "a" for the property) B = Set(files WITHOUT value "a" for the property) D = Mask file # of the same size as the file; we will put FF or bits set to 1 in places where the bit or byte may represent the property For all A, if the byte at the studied offset is identical, we set the byte in D to FF; otherwise, we set it to 00. For all B, if there exists a B that is identical to the byte in A, we set the byte in D to 0x00.

We repeat the operation for all values of the property. To add flexibility, we can introduce error tolerance for a dataset that may contain errors or the presence of specially encoded values.

The bit-wise approach poses an issue in comparing A and B. If the byte at position i is identical for A and B, then we remove the byte from the mask. But for bits, we need the exact size of the property's encoding because if the bit size is smaller, we may find values that are potentially identical for A and B, with the next or previous bit belonging to the property and differing. The same issue applies if the bit size is larger.

This is why it's necessary to create multiple masks for each bit size. Randomly added similarities or differences with an incorrect bit size of the property's encoding nullify the mask, so we test by incrementing sizes and keep only the mask that produces a result.

It's also important to note the overlap of the mask after a shift. For example, if we study bits from 0 to 4 and set the mask to 1111, we will subsequently study bits from 1 to 5 and potentially get 10000, which would erase the previous work. The idea would be to force bits to 1 and not reset them when they are set to 1 in the A and B comparison. We can potentially create two masks A <-> A and A <-> B and then use the logical AND.

Tools to Test

https://www.sweetscape.com/010editor/

Test entropy with binwalk (1. in Doku).

Doku

Reverse Engineering of binary File Formats

http://www.iwriteiam.nl/Ha_HTCABFF.html (Tools extraction is pending from the links)

https://github.com/tylerha97/awesome-reversing (A comprehensive list to study, determine what relates to binary reverse engineering - see if there are other "awesome .." lists)

https://beginners.re/RE4B-FR.pdf (check the detailed table of contents and find sections related to binary reverse engineering)

https://en.wikibooks.org/wiki/Reverse_Engineering/File_Formats